A systemic approach to the implementation of Industry 4.0

“The centrality of man in the era of Digital Transition” is the title, and the focus, of the latest work of the ANIE Automazione Industrial Software Working Group. The White Paper was written in collaboration with Raffaella Cagliano, Professor of People Management & Organization – Co-Director of the Industry 4.0 Transition Observatory, School of Management, Milan Polytechnic. In these pages we shall present the Executive Summary.

Digital technologies are today one of the central factors in the transformation of any organisation. In manufacturing, digitisation is often associated with the concept of Smart Manufacturing or Industry 4.0. 4.0 technologies not only enable significant productivity gains, but in some cases lead to a complete rethinking of the company’s business model and products. The recent COVID-19 pandemic was a sort of turning point in the process of digitisation of companies. Indeed, the companies which were able to flourish and have shown greater resilience are those that invested the most in digital technologies in the years before the pandemic. During the crisis, investment in digital transformation, even in the manufacturing industry, increased enormously.

Successful cases in the introduction of 4.0 technologies show that the real possibility of taking advantage of these opportunities passes through the development of a strategic vision with respect to the objectives targeted with digitisation and the production and business model to be implemented. Particularly, these companies tend to approach Industry 4.0 projects – or, more generally, the digitisation of processes – with a systemic and comprehensive approach, combining technological innovation, and the consequent adaptation of production processes, with profound organisational innovation. In the absence of such a systemic rethinking, companies tend to limit the consideration of organisational variables to a subsequent management of the consequences of the introduction of technologies on people and company structures. However, this approach leads to rather limited and sometimes even counterproductive results (“digitisation of waste”).

One of the most recurrent debates on the relationship between technology and work concerns a standpoint which contrasts the use of technology to replace human labour in processes or individual production activities on the one hand, and the use of technology to enhance people’s work capacity on the other. In this second perspective, technology constitutes a tool which enriches man’s potential, ‘increasing’ from time to time different capacities, such as physical strength or resistance (for instance, by means of exoskeletons), visual capacity (for example, by using virtual reality), data retrieval capacity (through smart devices connected to IoT technologies), data processing capacity through analytics and big data analysis tools, and so on.

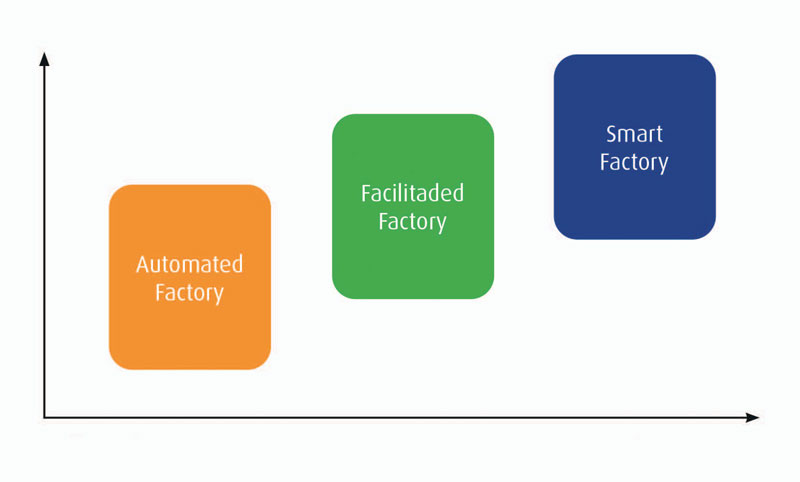

A recent survey carried out by the Milan Polytechnic’s Industry 4.0 Observatory proposed a summary of possible approaches to redesigning factory processes, represented in Figure 1, characterised by different degrees of replacement or enhancement of people’s work and, consequently, by different directions in rethinking the organisation. While in the Automated Factory model, 4.0 technologies – typically intelligent and/or collaborative robots and advanced manufacturing solutions – are introduced mainly to replace operators in performing typically manual tasks, in the Facilitated Factory and Smart Factory models, 4.0 technologies are implemented to support or enhance the work of operators by eliminating low added value activities and to provide more efficiently and effectively complete and detailed information on the tasks to be performed or procedures to be followed, up to enabling operators to control processes and make complex decisions autonomously (in the case of the Smart Factory).

Redesigning organisational models

The redesign of the organisation should concern:

– The organisation of work, that is, the design (or redesign) of the roles, responsibilities, decision-making and cognitive content, and autonomy of people working in operational processes;

– Consequently, the new skills needed both to correctly use the technologies themselves or the new methods associated with them, and to fill the newly defined roles, which often require widespread decision-making and data reading and interpretation skills;

– The organisational structure, that is, the design (or redesign) of organisational units linked to operational and transformation processes;

– The quality of work and organisational wellbeing, which is increasingly important considering companies’ growing sensitivity to issues of sustainability and social impact.

Observing several cases where 4.0 technologies have been introduced following a Facilitated and Smart Factory logic, the main directions of change – necessary or enabled – of the above mentioned organisational variables can be seen. First of all, an increase in the variety of tasks and the level of versatility of people can often be observed. Actually, operators tends to intervene less and less directly in the transformation process, as they are replaced by flexible automation technologies, and tend instead to have a wider set of tasks, often linked to activities of supervision, control, programming and management of systems and processes. The ‘scope’ of the task also tends to become broader, moving from responsibility for the individual workstation, to the machine, to responsibility for the entire workflow or process. Secondly, the content of the work tends to shift from the manual to the cognitive sphere, with significant contributions from operators in the decision-making processes and in the improvement and design of processes and individual technologies. This is often accompanied by a greater autonomy of the operators, who have a greater capacity for autonomous evaluation of the performance of the process and the results of their work thanks to data and the support of tools for their analysis and interpretation. This greater autonomy also implies greater responsibility of the operators and a request for a greater ability to interact both with higher hierarchical levels and with other organisational units and functions, even without intermediation with respect to their supervisors (in this case we can to all intents and purposes speak of Smart Factory). Wherever, on the other hand, there is a precise operational need to run machines and the production process, the simplification of interaction interfaces facilitates the training needed for this type of operators and makes it possible to build insertion paths for specific roles, creating the conditions for social inclusion through intense and focused training periods. A final relevant organisational element concerns the fact that the growing opportunity for integration of the various operational processes, from design to engineering, production and flow management, up to the interface with the downstream market, leads to a significant increase in collaboration and interaction between experts from different disciplines and, in some cases, also to the hybridisation between technical and operational roles and the emergence of new figures such as, for example, the operator-maintenance worker or the designer-engineer, and thus the dilution of the boundaries between technical and operational functions. All this leads both to the strengthening of basic skills and core knowledge of the manufacturing domain, and to the development of new skills linked to 4.0 technologies. As a consequence of the expansion of roles and the increase in autonomy and responsibility, management and decision-making skills, as well as transversal and relational skills, will also be increasingly necessary. Organisational structures also tend to be modified as a result of the introduction of 4.0 technologies, although the changes seem less marked. In keeping with the increased levels of autonomy of workers and work teams, a first direction of change concerns the streamlining of organisational structures, in terms of hierarchical levels and the presence of intermediate supervisors.

The design approach

Often the approach to Industry 4.0 projects tends to focus on the introduction of new technologies, only considering organisational variables at the time of implementation. This approach frequently leads to facing significant resistance to change. Conversely, the systems approach requires that technological and organisational factors be designed together. If technology is to support people’s work, technical and social variables should be designed together to exploit the joint advantage of the two systems and to design jobs and processes in which the potential of technology and people is fully exploited.

The joint design of the technology and the work system is also achieved through participatory approaches, where people are involved from the earliest stages of the project. Often, participation also includes a decision-making contribution from stakeholders in the various project phases, with the aim of making design choices which maximise the functionality and user acceptance of the technological solution and processes being innovated. When this level of involvement is reached, it also triggers a virtuous circle in which the manufacturing system benefits from the transformation even after the implementation of the technologies, since people are able to continuously improve the way they work and use technology, designing and adapting their role according to the potential progressively discovered in the technologies and data which have been made available. This idea of participation, involvement and widespread creativity is consistent with the principles of design thinking which can be seen used in the most advanced cases. In addition to individual participation, the role of organisational participation, achieved through the involvement of employee representatives and social stakeholders, is also very relevant. In short, an Industry 4.0 project must first of all start with a clear vision of the strategic objectives to be achieved, and must then develop through a systemic rethinking of processes and operating models, jointly designing the technical and organisational systems. In order to achieve these objectives, a broad involvement of all stakeholders involved and a broad individual and organisational participation are highly desirable. In conclusion, we would like to point out that the complete volume will be available from December 16th on the association’s website.

(Note: the article was taken from the Executive Summary of the White Paper “The Centrality of Man in the Digital Transition Era” edited by ANIE Automazione, www.anieautomazione.anie.it.)